By Randall Brown

Jordan Sangid’s path to analog signal processing research began in a different kind of “lab” from those in the Min Kao building, but just a few blocks away.

Sangid earned his first bachelor’s degree, in history with a religious studies minor, while also working as the live-sound engineer/bartender/manager at the Longbranch Saloon. This legendary, now-defunct bar and music venue was near campus on Cumberland Avenue, a.k.a. “The Strip.”

“I really liked working around music and meeting interesting people every night,” he said. “I thought that’s what I was going to do for a living, and that the history degree was just something I had on my résumé for when I was ready for the next level—whatever that was.”

The next level sneaked up on him via infrastructure needs specific to music halls. After many a weekend of rowdy rock’n’roll shows, he was left with a pile of broken microphone and speaker cables.

“The first couple of times we took the cables to Rik’s Music to be fixed, but it was too expensive and took too much time to get them back,” said Sangid. “I was gifted a $10 Radio Shack soldering iron by the owner of the bar, John Stockman, and my life was changed.”

He worked with electronics wiz John Stembridge, known around Knoxville as “The Sound Doctor,” to beef up the venue’s sound system, but grew more frustrated as ongoing problems grew bigger than he could fix on his own.

“I started taking night classes at Pellissippi State Community College to learn more about electronics and hoped to save the bar some money,” said Sangid.

He soon found himself at UT working towards a second bachelor’s degree. He gravitated toward the field of analog electronics and took classes with Benjamin Blalock, the Blalock-Kennedy-Pierce Professor in the Min H. Kao Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

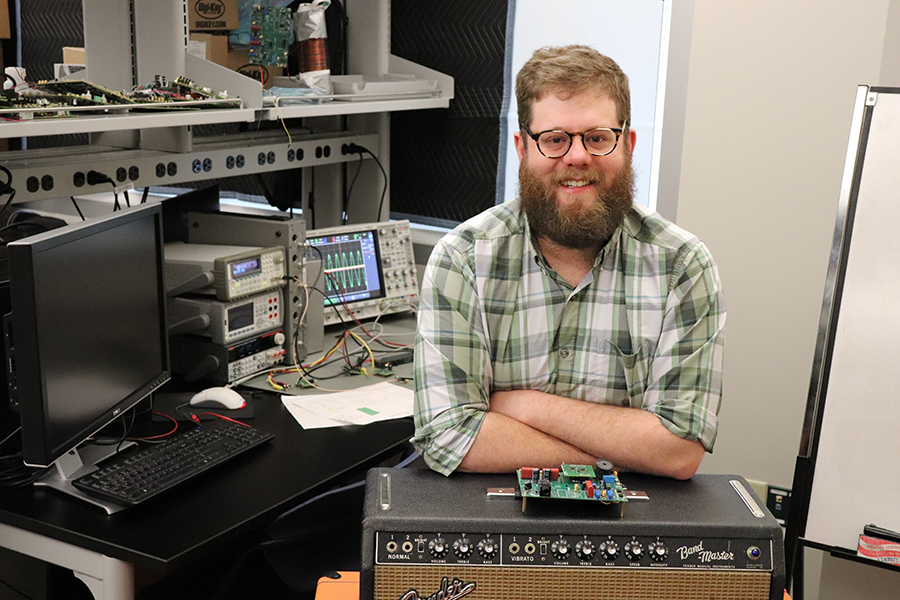

“Professor Blalock recruited me as an undergraduate research assistant to assist with printed circuit board (PCB) design and assembly,” said Sangid. “PCB design became my specialty and I’ve given direct assistance on nearly every PCB that has come through our lab since I’ve been here.”

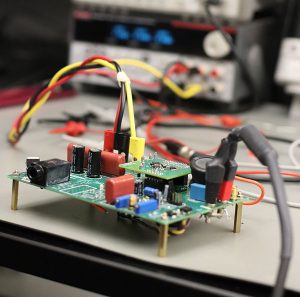

Close-up of an analog amplifier circuit made by Jordan Sangid.

He forged ahead into graduate studies. Blalock invited him to join his research team and pointed him toward the CURENT research center and the Department of Energy’s Wide Bandgap Traineeship, a fellowship for graduate students in power electronics. Sangid designed a GaN Class D Audio Amplifier as a Master’s thesis project within that traineeship.

“I participated as much as I could in CURENT activities to show the appreciation I had for the generous fellowship,” said Sangid. “For my two years, I served as the Chief of Professional Development in the CURENT Student Leadership Council and organized multiple events and seminars.”

His ongoing participation earned him notice as a 2019 Outstanding Graduate Teaching Assistant and his scholarship earned him a Bodenheimer Fellowship—a pair of accolades that a younger Sangid would not have expected.

“I was a big joker in high school and didn’t really try that hard,” he recalled. “I was always told that I wasn’t very good at math and science and I should probably study something else, so I did.”

He overcame those doubts, though, and has no regrets for his pre-engineering years.

“History was awesome,” he said. “It was like constant story time and I learned tons of Jeopardy facts.”

Sangid ultimately hopes that a career in analog electronics engineering helps him retain portions of his “rock’n’roll lifestyle.”

“My end goal has always been to have a job where I don’t have to wear a tie,” he said. “The more advanced degree you have in analog electronics, the less formal you have to dress. I’m targeting Crocs-with-socks now.”